Where The Bodies Are Buried

It’s not possible to be subversive in the United States any longer. Subversion is yet another sector of the economy that has been taken over by the government. In fact, subversion is Job One of the government. What used to be a small, highly profitable sector of the economy controlled by foreigners, has been legalized, commoditized, democratized and funded by the U.S. Congress. Programs have been established for foreigners to be massively imported and aided and abetted in all ways possible to destabilize and destroy the lives and livelihoods of the American people.

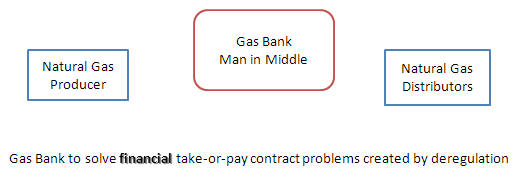

Following Ken Lay’s professional career is the path to understanding the means by which our critical infrastructure has been subverted and will be used ultimately to control us through what a friend of mine calls the “Man in the Middle” strategy. The Man in the Middle is the strategy they used to privatize our critical infrastructure - setting us up for conquer and control by foreign interests.

This story begins with pipelines for natural gas. I found a history of regulation of the natural gas and pipeline business. It's well written and brief and is necessary background for what follows:

The History of Regulation [Note: there is one link that doesn't work anymore but I recovered it from Wayback. It's the Public Utilities Holding Company Act (PUHCA) as of 1998. The summary description of it in the History provides enough information for now but I wanted to have the full document]

Public Utilities Holding Company Act of 1935 as of 1998

Ken Lay's Biography - abbreviated

-

Scholarship to University of Missouri, Professor Pinkney Walker convinced Lay to get a Masters in Economics

-

After graduation, he worked for Humble Oil, taking classes to get a doctorate.

-

1968 enlisted in the Navy. Professor Walker used connections to get Lay a position in Washington DC working in procurement.

-

1971 Pinkney Walker was appointed to the Federal Power Commission and he made Lay his Chief Assistant.

-

1972 appointed to Deputy Undersecretary for Energy reporting to Interior Secretary Rogers Morton.

-

1973 was hired by CEO W. J. Bowen of Florida Gas to be the VP in charge of corporate planning; rose to corporate president by 1976

-

1979 went to work for The Continental Group (curious move) - Florida property management company

-

1984 went to work for Houston Natural Gas (HNG) - helping to engineer the acquisition of Florida Gas - expanding HNG's pipelines all over the southeastern U.S.

-

1985 he became CEO of HNG

-

Excerpt from the written bio

In Omaha, Nebraska, Samuel F. Segnar, the CEO of the pipeline company InterNorth, and other company officers were distressed by the venture capitalist Irwin Jacobs, who had bought about one-third of their company's shares. They feared that Jacobs would take over the company. Thus, they looked for a way to turn InterNorth into a poisoned pill. They found at HNG a friendly, folksy CEO who was willing to cut a deal: InterNorth would purchase Houston Natural Gas for so much money that the newly merged company would have $5 billion in outstanding debt.

Segnar and his co-workers made an astonishing blunder, however: as part of their agreement with Houston Natural Gas they gave former HNG officers more seats on the new board of directors than were given to former InterNorth officers. The new company, dubbed HNG/InterNorth, bought out Jacobs's shares for $357 million, of which $230 million was taken from employees' retirement funds. In November 1985 the new company's board of directors fired Segnar and appointed Lay CEO. The entire turn of events became ironic when Jacobs said that he had never intended to take over InterNorth; he had just invested in what he regarded as a growth stock.

ENRON

In 1986, after senior executives debated new name possibilities, HNG/InterNorth became Enron, and Lay found another avenue to greater wealth: deregulation of the natural-gas industry. He used his Washington connections and had Enron make political donations in order to influence Congress to make natural gas an unregulated, tradeable commodity.In 1989, as natural gas was deregulated, Lay created the Gas Bank. The idea was to form a bridge between producer and consumer. Natural gas had been subject to large increases and drops in prices, and producers were reluctant to sign long-term contracts for fear that they would miss out on the next big upward spike in prices. The Gas Bank was intended to guarantee consumers long-term supplies at set rates while stockpiling reserves of natural gas bought from producers.

As an aside, it's doubtful that Segnar's "astonishing blunder" was actually a blunder. In doing this research, what has become obvious if one looks at patterns is that there is a clear pattern of Terminator CEO's who take the helm of healthy corporations then drive them into the dirt by making astonishing stupid decisions - and then claim to be just a silly dufus who accidently destroyed the company. It's like the Junk Bond King working from the inside to take a company down. McKinsey & Company seem to specialize in producing Terminator CEOs.

"Technocratic Deregulation Innovator"

In a 2005 article titled, Lay of the Land, Josh Harkinson wrote the following:

"The same laissez-faire, free-market ideas that had stung post boom Houston were transformed by Enron into the city's best notions of itself during the '90s. The company was a technocratic deregulation innovator, an oil-and-natural-gas outfit that had diversified into new markets, even broadband Internet. Its founders were perhaps a bit brash and arrogant, but they were also civically and philanthropically engaged. Enron was the new Houston."

Harkinson also wrote these paragraphs:

Near the pinnacle of Enron's success in the late '90s, CEO Ken Lay spoke to the editors of the corporate advice handbook Lessons from the Top. "I will always look for leadership over management skills in my senior people," Lay told them. "What we are trying to do is create an environment where we stimulate people to act like entrepreneurs, even inside a $30 billion company."

Nobody embodied this updated vision for the city better than Lay, who declined to speak to the Press. During the '90s, he was one of the most active members of the Greater Houston Partnership, a business group that has been alternately described as a civic organization and a shadow city government. "He was a man of action and he had an ability to move the ball," says GHP president Jim Kollaer. "And that was what everybody in the community needed."

The significance of those paragraphs will become apparent when looking at the history and legislation for deregulation of the utility companies which turns out to be for the purpose of privatization and market-based solutions for environmental problems which in implementation turns out to be War By Other Means - not just for natural gas, but also for electricity, water and telecommunications including telephone and broadband.

Bundled and Unbundled Product

The history of deregulation of the natural gas and pipeline companies, has the following sections that describe the process of using government regulation to solve a business problem while at the same time creating business opportunities to exploit both the producers and the consumers via a middle man:

In November of 1978, at the peak of the natural gas supply shortages, Congress enacted legislation known as the Natural Gas Policy Act (NGPA), as part of broader legislation known as the National Energy Act (NEA). Realizing that those price controls that had been put in place to protect consumers from potential monopoly pricing had now come full circle to hurt consumers in the form of natural gas shortages, the federal government sought through the NGPA to revise the federal regulation of the sale of natural gas. Essentially, this act had three main goals:

- Creating a single national natural gas market

- Equalizing supply with demand

- Allowing market forces to establish the wellhead price of natural gas

The Natural Gas Policy Act took the first steps towards deregulating the natural gas market, by instituting a scheme for the gradual removal of price ceilings at the wellhead. However, there still existed significant regulations regarding the sale of gas from an interstate pipeline to local utilities and local distribution companies (LDCs). Under the NGA and the NGPA, pipelines purchased natural gas from producers, transported it to its customers (mostly LDCs), and sold the bundled product for a regulated price. Instead of being able to purchase the natural gas as one product, and the transportation as a separate service, pipeline customers were offered no option to purchase the natural gas and arrange for its transportation separately.

Several events led up to the 'unbundling' of the pipelines' product. In the early 1980s, noticing that a significant number of industrial customers were switching from using natural gas to other forms of energy (for example, electric generators switching from natural gas to coal), several pipelines instituted what they called Special Marketing Programs (SMPs). Essentially, these programs, which were approved by FERC, allowed industrial customers with the capability to switch fuels the right to purchase gas directly from producers, and transport this gas via the pipelines. However, SMPs were found discriminatory by the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals in several 1985 cases. The court ruled that SMPs were discriminatory in that no other customer of the pipelines had the ability to purchase their own natural gas and transport it via pipeline. As a result of this, SMPs were eliminated on October 31, 1985.

However, the practice of allowing customers to purchase their own gas, and use pipelines only as transporters rather than merchants, was not abandoned. In fact, it became part of FERC policy to encourage this separation by way of Order No. 436.

FERC Order No. 436In 1985, FERC issued Order No. 436, which changed how interstate pipelines were regulated. This order established a voluntary framework under which interstate pipelines could act solely as transporters of natural gas, rather than filling the role of a natural gas merchant. This order provided for all customers the same possibilities that the SMPs of the early 1980s had afforded industrial fuel-switching customers, thus avoiding the discrimination problems of the earlier SMPs. Essentially, FERC allowed pipelines, on a voluntary basis, to offer transportation services to customers who requested them on a first come, first served basis. The interstate pipelines were barred from discriminating against transportation requests based on protecting their own merchant services. Transportation rate minimums and maximums were set, but within those boundaries the pipelines were free to offer competitive rates to their customers. Although the framework established by Order 436 was voluntary, all of the major pipeline systems eventually took part.

It should be noted that new regulation doesn't change existing contracts. Backing up to the impacts of the 1978 regulations and the impact on the market:

Thus the NGPA allowed for more competitive prices at the wellhead. However, many members of the industry were unprepared for the corresponding drop in demand. The pipelines, used to the era of curtailment, were quick to sign up for long-term 'take-or-pay' contracts. These contracts required the pipelines to pay for a certain amount of the contracted gas, whether or not they can take the full contracted amount. While the NGPA did spur investment in the discovery of new natural gas reserves, the increasing wellhead price, mixed with the eagerness of pipelines to deliver as much natural gas as possible, led to a situation of oversupply.

Continuing with FERC Order No. 436

The movement towards allowing pipeline customers the choice in the purchase of their natural gas and their transportation arrangements became known 'open access'. Order No. 436 thus became generally known as the Open Access Order.

While the general thrust of Order 436 was upheld in Court, several problems arose regarding the 'take-or-pay' contracts under which the pipelines were still obliged. Given these problems, and under remand from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, FERC issued Order No. 500 in 1987. This order essentially encouraged interstate pipelines to buy out the costly take-or-pay contracts, and allowed them to pass a portion of the cost of doing so through to their sales customers. The LDCs to which these costs were passed through were allowed by state regulatory bodies to further pass them on to retail customers. However, the open access provisions of Order No. 436 remained intact.

Ken Lay was a Technocrat. In his past, he had been the Deputy Undersecretary of Energy so he had the understanding of the regulations; he had connections in the Department of Energy, and in 1985, he was the CEO of Houston Gas Company which put him in position to exploit all of the above which is what led him to propose the Gas Bank to provide relief to the distributors and consumers who were in 'Take or Pay' contracts.

There are many sides to this story and

each gives a different point of view on what happened, why it happened

and the consequences of it so a person's view depends on the source of

their information. In financial circles, this could be described

as "creating space for innovation" in the energy markets.

Deregulation created an opportunity for a parasitic system of control

and price manipulation via a middle man which is an indirect form of

theft from the end consumers because they are the ones who pay for the

parasites. And because of the nature of the public utilities

business that provides essential services, the consumers have no choice

but to pay.

What the above actually is - is regulatory racketeering. The Man in the Middle has no skin in the game in terms of the product, but he has all the power because he is between the Producers and the Distributor-Consumers. That was the beginning of Enron and the creation of an asset-light, virtual energy company.

The following is a special report on Enron, "Enron: virtual company, virtual profits".

This link is to a powerpoint that was prepared by Frank A. Wolak, Department of Economics, Stanford University. I'm including it because it was an analysis of Enron's business model with a lot of important questions.

Arbitrage, Risk Management and Market Manipulation: What Do Traders Do and When is it Illegal?

Why did I take such pains to describe the technocratic means by which Enron was created? I did that because Enron wasn't an ordinary business and Ken Lay was not an ordinary business man. Enron was a global economic WMD created for the purpose of privatization of public utilities as a strategy of the "market-based" Green Pirates of the Environmental Defense Fund and their "movement" which is actually War by Other Means.

One more thing - here is a brief profile of Richard Kinder who quit his job as CEO of Enron in 1996. Kinder was replaced by Jeff Skilling who came from McKinsey & Company.

Absorb the

above and integrate it into your thinking because there is more to the

story that will be presented in Part 2.

Vicky Davis

December 12, 2011

Link to Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

1998 World Bank Report:

Development of Natural Gas and Pipeline Capacity Markets in the U.S.