National Subversives Security Act of 1947

If the National Security Act of 1947 were accurately named, it would have been called the National Subversives Security Act because it established the administrative framework for subversives to the U.S. Constitution and our country to operate under the color of law within the U.S. government. The beauty of this arrangement is that there is a public face to it that is ostensibly diplomatic and open dealing with foreign nations, but there is also a dark and covert side and while they allegedly are not allowed to operate domestically, they do act domestically through the big private Foundations - implementing the policies of the United Nations Organizations. Understanding that explains how United Nations policies are coordinated and implemented in the United States.

From the beginning of this country's history, there have been two factions - Internationalists and Nationalists. The Nationalists were our Founders. The Internationalists were the Tories - enemies of independence. Cordell Hull, Secretary of State from 1933-1944, was one such Internationalist. For his entire career in public life, he worked to subvert the sovereignty and Independence of the United States. From the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, the lowering of tariffs on imports and replacement revenue in the form of income taxes on the American people to the Dumbarton Oaks conferences where he led the effort to write the draft charter for the United Nations, Cordell Hull betrayed his country and fellow Americans. In 1945 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1945 as "The Father of the United Nations".

President Roosevelt recognized the inherent weaknesses of the League of Nations, but faced with the reality of another world war, also saw the value of planning for the creation of an international organization to maintain peace in the post-World War II era. He felt that this time, the United States needed to play a leading role both in the creation of the organization, and in the organization itself. Moreover, in contrast to the League, the new organization needed the power to enforce key decisions. The first wartime meeting between British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt, the Atlantic Conference held off the coast of Newfoundland in August 1941, took place before the United States had formally entered the war as a combatant. Despite its official position of neutrality, the United States joined Britain in issuing a joint declaration that became known as the Atlantic Charter. This pronouncement outlined a vision for a postwar order supported, in part, by an effective international organization that would replace the struggling League of Nations. During this meeting, Roosevelt privately suggested to Churchill the name of the future organization: the United Nations.

[Roosevelt died before the San Francisco conference creating the United Nations. Truman took over.]

The San Francisco Conference, formally known as the United Nations Conference on International Organization, opened on April 25, 1945, with delegations from fifty countries present. The U.S. delegation to San Francisco included Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr., former Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and Senators Tom Connally (D-Texas) and Arthur Vandenberg (R-Michigan), as well as other Congressional and public representatives...

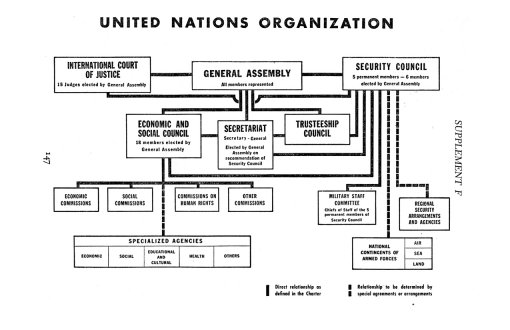

At San Francisco, the delegates reviewed and often rewrote the text agreed to at Dumbarton Oaks. The delegations negotiated a role for regional organizations under the United Nations umbrella and outlined the powers of the office of Secretary General, including the authority to refer conflicts to the Security Council. Conference participants also considered a proposal for compulsory jurisdiction for a World Court, but Stettinius recognized such an outcome could imperil Senate ratification. The delegates then agreed that each state should make its own determination about World Court membership. The conference did approve the creation of an Economic and Social Council and a Trusteeship Council to assist in the process of decolonization, and agreed that these councils would have rotating geographic representation. The United Nations Charter also gave the United Nations broader jurisdiction over issues that were “essentially within” the domestic jurisdiction of states, such as human rights, than the League of Nations had, and broadened its scope on economic and technological issues.

The decision to create a World

Organization was agreed to at the Crimea Conference in an

agreement commonly referred to as the

Yalta

Agreement.

At the Truman Library website there is a transcript of an Oral History given by J. Wesley Adams. Adams was a Technical Advisor to the U.S. Delegation at United Nations Conference on International Organization, 1945. The following are excerpts from that transcript (emphasis added):

MCKINZIE: The issue that you mentioned that as an overriding issue at the Conference -- namely, the veto -- was originally insisted upon by the United States as a means of making the Senate feel that the United States would not be dragooned into any kind of international action. The veto -- even though the Soviet used it most the first years -- was nonetheless a necessary thing for the United States.

ADAMS: I was never personally involved in discussions within the American Government on this particular point and obviously it was decided at the Presidential level. But I always assumed that the United States would itself have insisted upon the veto, and of course agreement on the veto was reached at the Yalta Conference. The feeling, I think, at the San Francisco Conference was that this system was not going to work unless the big powers agreed... So, the veto was built on this assumption that the two powers must agree. Three other countries also had the veto but militarily they were very weak, had been practically prostrated by the war (the British, and the French, and China). What we are really talking about was the United States and Soviet Union.

...You had a feeling in the Department at that time that the shots were being called by Edward Stettinius? Or was it more of a committee operation? Did you think Stettinius was strong?

ADAMS: No. I had the feeling that Mr. Stettinius was taking his directions from the White House, and relying heavily on bureaucratic advice. Mr. Stettinius, of course, came into this picture very late in the game. Cordell Hull had been Secretary right up to about the time of the Conference. Hull had been at Dumbarton Oaks the fall before. I would say that below the President it was a committee operation. Yes. Because there were very strong advisers to the U. S. delegation, as I mentioned, the Senators and the Congressmen, the top people in the State Department, Defense Department, Treasury, and Mr. Stettinius. I think they worked as a team.

MCKINZIE: When you came back to Washington after the San Francisco Conference, did you immediately start work then on other international conferences?

ADAMS: Yes. The whole inter-departmental staff then got to work on preparing the actual U. S. participation in the United Nations itself. In the following winter the first meeting of the General Assembly of the United Nations met in London. Our Bureau then became the Office of United Nations Affairs, our job being to backstop the U. S. delegation to various U. N. bodies and help prepare the U. S. position on various issues.

ADAMS: To change the subject, I would mention the prominence or notoriety subsequently achieved by members of the Office of International Security Affairs in which I worked at that time. It was quite remarkable. In charge of the whole U.N. office in State was Alger Hiss, who had been the Secretary General of the United Nations Conference and was subsequently to be a key figure in the McCarthy era, the pumpkin papers and Whittaker Chambers. Our immediate chief was Joseph Johnson who was later to become head of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The United Nation Charter was signed on June 26, 1945.

Source: The World Charter and the Road to Peace

Author: Stuart Chevalier

1946, The Ward Ritchie Press, Los Angeles

The International Nanny

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO):

"Since wars begin in the minds of men,

it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must

be constructed"

According to a history paper

on UNESCO written by Raymond E. Wanner, titled

"The United States and UNESCO: Beginnings (1945) and New

Beginnings (2005) [pdf],

the planning for post war reconstruction of the education

system began as early as 1941 and resulted in UNESCO.

If you consider the efforts to create an international

system of education by some groups, the efforts were

actually underway even before the war. Excerpts from

Wanner's paper (emphasis added):

THE CONFERENCE OF ALLIED MINISTERS OF EDUCATION

The London Conference and, ultimately UNESCO itself, evolved from sessions of the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME). As early as 1941 the so-called London International Assembly had provided a forum for displaced representatives of like-minded nations to discuss common problems informally. R. A. Butler, President of the British Board of Education, who was greatly concerned with postwar reconstruction on the continent, formalized this gathering into the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education in November 1942.

Washington saw the elements of a future UNESCO in a resolution adopted in January 1943 that called for a "United Nations Bureau for Educational Reconstruction" whose purpose would be to meet urgent needs…in the enemy-occupied countries.9

Washington’s priority at the time was postwar security and the urgent creation of the United Nations as a multilateral security agency. President Roosevelt believed that to delay adoption of the UN Charter until peace was established ran the risk of nations perceiving international cooperation as less urgent and the United Nations creation as less certain.11 CAME, consequently, was of considerably lower priority, and the United States maintained only an observer presence in the person of Richard A. Johnson a young, London-based diplomat. 12

WASHINGTON’S AWAKENING AND J. WILLIAM FULBRIGHT

Great power politics ultimately drew Washington into the CAME process....

Washington grew uncomfortable also with what it considered overly aggressive British leadership in the creation of the new educational and cultural organization. 13 It was time for Washington to take CAME seriously; it did so with vigor.

in April 1944, with President Roosevelt’s personal endorsement, it sent a delegation led by then Congressman J. William Fullbright that included Assistant Secretary of State MacLeish, Commissioner of Education John Studebaker, Stanford University Dean, Grayson Kefauver, Vassar College Dean Mildred Thompson and Ralph Turner with instructions to participate fully in CAME’s efforts to sketch out a constitution for the new organization.

The delegation had enormous influence on the shape of the future UNESCO. Elected Conference Chair, Fulbright immediately enlarged the CAME drafting committee, had it meet in open sessions and ruled that each country represented have one vote regardless of its size or number of representatives. He then seized the initiative by having his own delegation draft a parallel conference working paper. Kefauver, Studebaker and others worked until midnight over a weekend and, drawing on the existing United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) constitutions, produced a new document, "Suggestions for the Development of the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education into the United Nations Organization for Educational and Cultural Reconstruction." 15 Their text soon became the meeting’s working text.

The political insights of the American delegation were significant in that they shifted the conceptual base of UNESCO from postwar reconstruction of schools and protection of physical cultural heritage to peace and security. Fulbright, for example, remarked that international efforts in education could "do more in the long run for peace than any number of trade treaties." And again: "Let there be understanding between the nations of each other and each other’s problems, and the causes of quarrel disappear."16 MacLeish, the poet, later articulated the new reality concisely. UNESCO’s role would be "to construct the defenses of peace in the minds of men." It was to be a security agency; its weapon, intercultural dialogue.

With war still waging, it would take months and a change of leadership at the Department of State -- Edward R. Stettinius Jr. replacing Cordell Hull as Secretary –- for the momentum toward the creation of UNESCO to be tapped.18 Through late 1944 and early 1945 Washington’s multilateral priority remained the creation of the United Nations.

THE MACLEISH DELEGATION

On April 11, 1945, the very day CAME released its revision of the April 1944 draft constitution, Washington unilaterally submitted a parallel revised draft to the British, French, Soviet and Chinese governments for comment. Both the CAME and the Washington texts foresaw the creation of a permanent United Nations Organization for Educational and Cultural Cooperation.

Like J. William Fulbright’s delegation eighteen months earlier, MacLeish’s was to make a lasting contribution to the future UNESCO. At its morning meeting November 3, the delegation agreed to recommend that ""United Nations" should be part of the title, that "Scientific" be added… and that the full name which abbreviates as UNESCO be adopted."21

[Wilkinson] "In these days, when we are all wondering, perhaps apprehensively, what the scientists will do to us next, it is important that they should be linked closely with the humanities and should feel they have a responsibility to mankind for the result of their labours." The Conference agreed the following day to include science in UNESCO’s mandate.22 The United States then urged close collaboration with the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), a collaboration that continues to this day.23.

...there was fundamental philosophical and political agreement that the new organization should be a forum where the peoples of the world, themselves, and not just their governments or the elite could interact. Thus, the high importance given by both countries to National Commissions for UNESCO as essential bridges between governments and civil society.

PROGRAM PRIORITIES

MacLeish returned often to the theme of using the new tools of mass communication, film, radio, telegraph, and the press, "to enlighten the peoples of the world in a spirit of truth, justice and mutual understanding." It was to be the first and most important program priority.43 Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, William Benton, urged UNESCO to study how fundamental education could be provided by radio and films. Later, in the U.S. Senate, he would propose a "Marshall Plan for Ideas.44

The second program priority was to promote international cooperation in science, in particular by having the new organization establish close ties with the International Council of Scientific Unions to permit scientists from every country to exchange information and to work together. Again, the fundamental issue of free flow of ideas was at play as well as the veiled affirmation that a way needed to be found to use the breakthrough scientific knowledge behind the destruction at Hiroshima to serve humanity.

The third program priority was to promote "Basic Education," with an emphasis on adult education through close cooperation with existing public and private programs. The goal was less to address illiteracy, as such, than to prepare the public for its responsibilities for active life in democratic societies and to arm it against ideologies that could lead to war. The American program proposals were adopted by acclamation.45

THREE PROBLEMS

A number of delegates, with the Chinese, Greek, Yugoslav and Polish delegates the most outspoken, asked how UNESCO could construct the defenses of peace in the minds of men without first meeting basic human needs of food and shelter and the physical infrastructure of civilized life.... Constructing the defenses of peace would require a worldwide, coordinated, and mutually dependent effort to address fundamental human needs as well as the aspirations of the human spirit. To succeed, UNESCO, other agencies, the international banks and governments would need to work in consort.

Initially, the plan for the Economic and Social councils of the United Nations was to include only Education and Culture. According to a paper written by Gail Archibald, the 'S' for Science was included as a result of the efforts of Joseph Needham:

"During the 1920s, international scientific cooperation had been rekindled with the restoration of peace after the First World War. The League of Nations’ International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation, founded in Paris in 1926, included a section devoted to Scientific Information and Scientific Relations. Among the activities of the International Bureau of Education, established in Geneva (Switzerland) the previous year, was scientific research. In the nongovernmental sector, the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) would be founded in Brussels (Belgium) in 1931.

Then the Second World War broke out. By 1943, however, Allied victories encouraged politicians to turn their attention to post-war planning. On both sides of the Atlantic, non-governmental projects proposed the creation of an international organization for education.

The British Government sent Needham to China in February 1943 as a representative of the Royal Society to consolidate Anglo–Chinese cultural and scientific relations. In December of the same year, Needham wrote to China’s Foreign Minister elaborating his idea of international scientific cooperation: ‘The time has gone by when enough can be done by scientists working as individuals or even in groups organized as universities, within individual countries … Science and technology are now playing, and will increasingly play, so predominant a part in human civilization that some means whereby science can effectively transcend national boundaries is urgently necessary’. Needham’s immediate goal was the transfer of advanced basic and applied science from highly industrialized Western countries to the less industrialized ones, ‘but’, he assured, ‘there would be plenty of scope for traffic in the opposite direction too’.

....

Invitations were sent out during the first week of August 1945 to attend the United Nations Conference for the Establishment of an Educational and Cultural Organization to be held in London November 1-16, 1945. Atomic bombs dropped on Japan, the 6th and 9th of the same month ended the 2nd world war...

On 5 November, the Conference divided itself into Commissions. The First Commission was charged with drafting the Title, Preamble and Aims and Functions of the new organization. It was the American delegate who proposed that it be called the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. After hesitating for twenty-four hours, the commission decided in favour of the UNESCO title, which simultaneously served as an instruction to insert the word ‘science’ in the text of the Constitution wherever indicated. For example, ‘The purpose of the Organization is to contribute to peace and security by promoting collaboration among the nations through education, science and culture’.

The "Constitution" for UNESCO was signed on November 16, 1945.

U.S. State Department

In the previous report (Biggest, Big Lie) there was a link to the U.S. State Department website and it was noted that Secretary of State George Kennan established a new group named the Policy Planning Staff. Their function was planning and management of U.S. engagement (Marshall Plan) in the recovery of Europe following World War II. The objective of the Marshall Plan was to rebuild Western Europe as an economically integrated region governed by a regional council. It was decided that the U.S. involvement would be through the United Nations rather than direct management by the U.S. government. The Policy Planning Staff of the State Department was the liaison between the United States and the United Nations - coordinating domestic policy with the United Nations initiatives. Because of the magnitude of the Marshall Plan and involvement with an association of governments (United Nations), the National Security Council was created by the National Security Act of 1947 (amended 1949).

The National Security Act of 1947 mandated a major reorganization of the foreign policy and military establishments of the U.S. Government. The act created many of the institutions that Presidents found useful when formulating and implementing foreign policy, including the National Security Council (NSC). The Council itself included the President, Vice President, Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, and other members (such as the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency), who met at the White House to discuss both long-term problems and more immediate national security crises. A small NSC staff was hired to coordinate foreign policy materials from other agencies for the President...

The act also established the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which grew out of World War II era Office of Strategic Services and small post-war intelligence organizations. The CIA served as the primary civilian intelligence-gathering organization in the government. Later, the Defense Intelligence Agency became the main military intelligence body. The 1947 law also caused far-reaching changes in the military establishment. The War Department and Navy Department merged into a single Department of Defense under the Secretary of Defense, who also directed the newly created Department of the Air Force. However, each of the three branches maintained their own service secretaries. In 1949 the act was amended to give the Secretary of Defense more power over the individual services and their secretaries.

In 1949, the NSA Act of 1947 was amended to reduced the influence of the Department of Defense by removing the three service secretaries (army, navy, air force) from its membership.

White House History of the National Security Council (NSC)

The National Security Act of July 26, 1947, created the National Security Council under the chairmanship of the President, with the Secretaries of State and Defense as its key members, to coordinate foreign policy and defense policy, and to reconcile diplomatic and military commitments and requirements. This major legislation also provided for a Secretary of Defense, a National Military Establishment, Central Intelligence Agency, and National Security Resources Board. The view that the NSC had been created to coordinate political and military questions quickly gave way to the understanding that the NSC existed to serve the President alone. The view that the Council's role was to foster collegiality among departments also gave way to the need by successive Presidents to use the Council as a means of controlling and managing competing departments.

In 1949, the NSC was reorganized. Truman directed the Secretary of the Treasury to attend all meetings and Congress amended the National Security Act of 1947 to eliminate the three service secretaries from Council membership and add the Vice President(who assumed second rank from the Secretary of State(and the Joint Chiefs of Staff who became permanent advisers to the Council. NSC standing committees were created to deal with sensitive issues such as internal security. The NSC staff consisted of three groups: the Executive Secretary and his staff who managed the paper flow; a staff, made up of personnel on detail, whose role was to develop studies and policy recommendations (headed by the Coordinator from the Department of State); and the Consultants to the Executive Secretary who acted as chief policy and operational planners for each department or agency represented on the NSC.

The National Security Council was created by Public Law 80(253, approved July 26, 1947, as part of a general reorganization of the U.S. national security apparatus.

by Francisco Gil-White

Did the National Security Act of 1947 destroy freedom of the press?

"The National Security Act (passed in 1947) allows US Intelligence to begin any action, at any time, without asking anybody. In addition, US Intelligence may postpone indefinitely any report of such activity simply by claiming that making the report would harm the "national security" of the United States. This is a recipe for absolute power. It follows that the National Security Act of 1947 gave US Intelligence the power -- if not the explicit authority -- to corrupt the press in secret. This article will argue, and document, that this is precisely what US Intelligence has done. Naturally, this raises the sharpest possible questions about the integrity of US democracy." [More]

The answer to that question is obviously 'YES' when you understand the purpose of the National Security Act of 1947 and the signing of the United Nations charter and the UNESCO Constitution was to subvert the Constitution of the United States for the ultimate goal of creating a World Government. The National Security Act created the subversive council at the highest level of government to steer - by whatever means necessary, U.S. domestic and foreign policy toward the end goal of a World Government. In doing that, they committed treason by swearing allegiance to a collective foreign power - an association of governments and they did it behind the shield of "national security".

The schizophrenia is apparent in a speech given by Secretary of State James F. Byrnes at the end of the London Conference when the UNESCO Constitution was signed. And the fraud becomes most apparent when he begins talking about trade and economics. Business - by definition is competitive and predatory. It's the nature of the beast and yet he talks about it as if it's the key to world peace. And when he gets to the part about overcoming trading blocs it's absolutely laughable because the whole idea behind the Marshall Plan and the aid to Britain was to create the European Union which is in fact, a political organization designed to create an economic unit - a trading bloc.

The following are only excerpts, but this speech is really a MUST READ speech: [PDF]

JAMES F. BYRNES ON ATOMIC ENERGY AND

INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Part of an Address broadcast on "Home-Coming Day," November 16, 1945.

....From the day the first bomb fell on Hiroshima, one thing has been clear to all of us. The civilized world cannot survive an atomic war.

This is the challenge to our generation. To meet it we must let our minds be bold. At the same time we must not imagine wishfully that overnight there can arise full-grown a world government wise and strong enough to protect all of us and tolerant and democratic enough to command our willing loyalty.

Accordingly, the President of the United States and the Prime Ministers of Great Britain and Canada-the partners in the historic scientific and engineering undertaking that resulted in the release of atomic energy-have taken the first step in an effort to rescue the world from a desperate armament race.

In their statement, they declared their willingness to make immediate arrangements for the exchange of basic scientific information for peaceful purposes. Much of this kind of basic information essential to the development of atomic energy has already been disseminated. We shall continue to make such information available.

In addition to these immediate proposals the conference recommended that at the earliest practicable date a Commission should be established under the United Nations Organization. This can be done within sixty days.

It would be the duty of this Commission to draft recommendations for extending the international exchange of basic scientific information for peaceful purposes, for the control of atomic energy to the extent necessary to insure its use only for peaceful purposes, and for the elimination from national armaments of atomic weapons and of all other weapons adaptable to mass destruction.

Without the united effort and unremitting cooperation of all the nations of the world, there will be no enduring and effective protection against the atomic bomb. There will be no protection against bacteriological warfare, an even more frightful method of human destruction.

Atomic energy is a new instrument that has been given to man. He may use it to destroy himself and a civilization which centuries of sweat and toil and blood have built. Or he may use it to win for himself new dignity and a better and more abundant life.

If we can move gradually but surely toward free and unlimited exchange of scientific and industrial information, to control and perhaps eventually to eliminate the manufacture of atomic weapons and other weapons capable of mass destruction, we will have progressed toward achieving freedom from fear.

But it is not enough to banish atomic or bacteriological warfare. We must banish war. To that great goal of humanity we must ever rededicate our hearts and strength.

To help us move toward that goal we must guard not only against military threats to world security but economic threats to world well-being. Political peace and economic warfare cannot long exist together. If we are going to have peace in this world, we must learn to live together and work together. We must be able to do business together.

Trade blackouts, just as much as other types of blackouts, breed distrust and disunity. Business relations bring nations and their peoples closer together and, perhaps more than anything else, promote good will and determination for peace.

We must not only oppose these exclusive trading blocs but we must also cooperate with other nations in removing conditions which breed discrimination in world trade.

Whatever foreign loans we make will of course increase the markets for American products, for in the long run the dollars we lend can be spent only in this country.

The countries devastated by the war want to get back to work. They want to get back to production which will enable them to support themselves. When they can do this, they will buy goods from us. America, in helping them, will be helping herself.

We cannot play Santa Claus to the world but we can make loans to governments whose credit is good, provided such governments will make changes in commercial policies which will make it possible for us to increase our trade with them.

These are the same liberal principles which my friend and predecessor, Cordell Hull, urged for so many years.

They are based on the conviction that what matters most in trade is not the buttressing of particular competitive positions, but the increase of productive employment, the increase of production, and the increase of general prosperity.

The reasons for poverty and hunger are no longer the stinginess of nature. Modern knowledge makes it technically possible for mankind to produce enough good things to go around. The world's present capacity to produce gives it the greatest opportunity in history to increase the standards of living for all peoples of the world.

We intend to propose that commercial quotas and embargoes be restricted to a few really necessary cases, and that discrimination in their application be avoided.

We intend to propose that tariffs be reduced and tariff preferences be eliminated. The Trade Agreements Act is our standing offer to negotiate to that end.

We intend to propose that subsidies, in general, should be the subject of international discussion, and that subsidies on exports should be confined to exceptional cases, under general rules, as soon as the period of emergency adjustment is over.

We intend to propose that governments conducting public enterprises in foreign trade should agree to give fair treatment to the commerce of all friendly states, that they should make their purchases and sales on purely economic grounds, and that they should avoid using a monopoly of imports to give excessive protection to their own producers.

We intend to propose that international cartels and monopolies should be prevented by international action from restricting the commerce of the world.

We intend to propose that the special problems of the great primary commodities should be studied internationally, and that consuming countries should have an equal voice with producing countries in whatever decisions may be made.

We intend to propose that the efforts of all countries to maintain full and regular employment should be guided by the rule that no country should solve its domestic problems by measures that would prevent the expansion of world trade, and no country is at liberty to export its unemployment to its neighbors.

We intend to propose that an International Trade Organization be created, under the Economic and Social Council, as an integral part of the structure of the United Nations.

We intend to propose that the United Nations call an International Conference on Trade and Employment to deal with all these problems.

In preparation for that Conference we intend to go forward with actual negotiations with several countries for the reduction of trade barriers, under the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act.

By proposing that the United Nations Organization appoint a commission to consider the subject of atomic energy and by proposing that the Organization likewise call a conference to enable nations to consider the problems of international trade, we demonstrate our confidence in that Organization as an effective instrumentality for world cooperation and world peace.

After the First World War we rejected the plea of Woodrow Wilson and refused to join the League of Nations. Our action contributed to the ineffectiveness of the League.

Now the situation is different. We have sponsored the United Nations Organization. We are giving it our wholehearted and enthusiastic support. We recognize our responsibility in the affairs of the world. We shall not evade that responsibility.

With other nations of the world we shall walk hand in hand in the paths of peace in the hope that all peoples can find freedom from fear and freedom from want.

Vicky Davis

11/11/08

- To Be Continued -